Six Weeks to Success: Clear Roles & Responsibilities

Caroline Kemp Lopez, Sara Taylor, & James Cryan: Originally published 5/2/18 on Medium

In 2015, Rocky Mountain Prep had two schools and was preparing to open 2 more. James Cryan, RMP’s founder and chief executive officer, knew he couldn’t afford any mis-hires: “We had to get disciplined about what we needed specific roles to accomplish.”

Inspired by Topgrading (a methodology articulated in the book, Who: The A Method for Hiring), RMP decided to adopt structured scorecards in its central office and school leadership hiring processes.

In contrast to a typical job description, the scorecard:

Explicitly defines what success looks like for the specific role

Provides a clear rubric which the hiring team can use to evaluate a candidate’s past performance against the needs of the current role

Serves as the basis for performance management and professional development once the new hire comes onboard

Sara Taylor, RMP’s chief talent officer, says, “We now can hire the right person for the role based on evidence about what she’s actually done in the past — instead of guessing what we think she could do.”

Sara and James share how RMP uses scorecards to recruit the best people.

Define What Success Looks Like for the Role

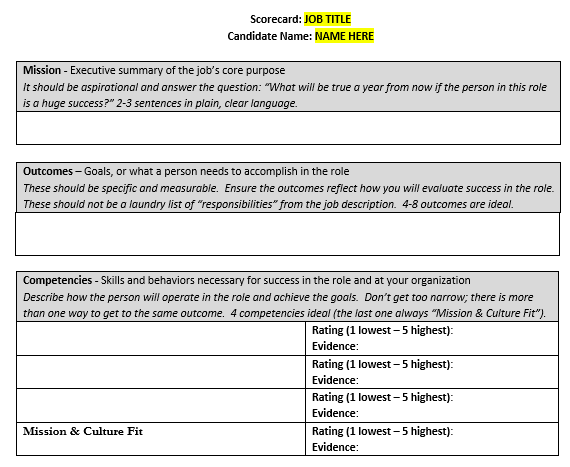

Many job descriptions read as a laundry list of the tasks for which a new hire will be responsible. In contrast, structured scorecards serve as the blueprint for a role’s first 1–3 years by outlining the measurable outcomes that the new hire is expected to accomplish, as well as the competencies required to get the job done. (See scorecard template here.)

When crafting a scorecard, RMP starts with the key outcomes — the 4–8 specific goals for which the hire will be held accountable.

The hiring team asks: “What are we going to look at in a year to determine if the new hire is a top performer?” The key is to focus on outputs, not inputs. “Produce a monthly newsletter” is an input. “Increase newsletter readership by 20% in year 1” is an output.

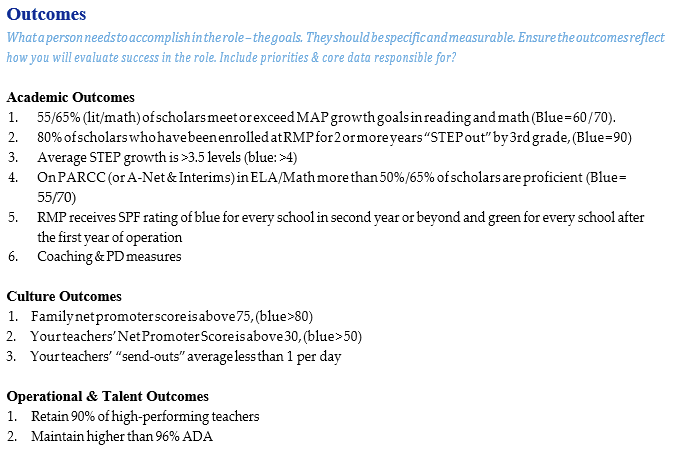

For example, RMP’s assistant principals of instruction are responsible for a variety of academic, culture, and operational goals — including ensuring 65% of scholars meet or exceed MAP growth goals in math and maintaining 90+% teacher retention. (See sample RMP assistant principal of instruction scorecard.)

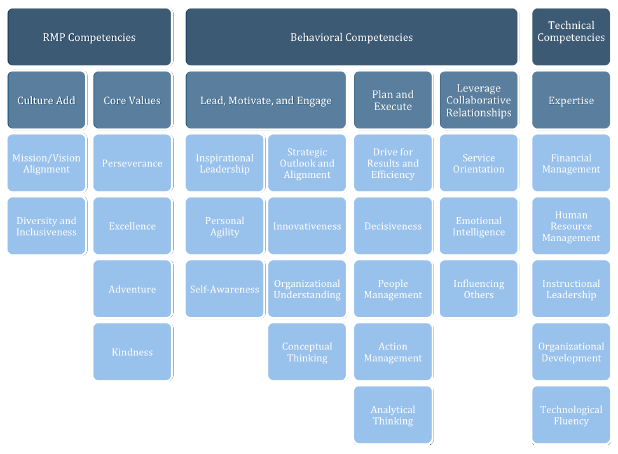

RMP then outlines the skills and behaviors that are necessary for success in the role and at the organization. These competencies describe how the new hire will achieve the desired outcomes.

RMP draws from its own competency library that is codified to ensure consistency across roles and levels. (See also EdFuel’s “Blueprint for Success” competency maps for finance, operations, talent, academics, development, advocacy, and data.)

In addition to 4–6 “position-specific” behavioral or technical competencies, every scorecard includes two organization-wide “core” competencies. These describe mission and culture fit, such as RMP’s PEAK values — perseverance, excellence, adventure, and kindness.

Sara cautions against getting too prescriptive: “There is more than one way to do a job. Focus only on the most important competencies for each role.”

Sample Competencies for Assistant Principal Role

Finally, Sara and the hiring manager write a succinct overview of the job’s mission, or core purpose. This statement is aspirational, connecting the role with the broader organizational mission and priorities.

Sample RMP Chief Academic Officer Mission Statement

Once completed, the scorecard informs the sourcing strategy and target candidate profiles. In addition, the scorecard can serve as an external recruitment tool, replacing the standard job description. IDEA Public Schools, another scorecard aficionado, added some organizational background and qualifications to its recent vice president of HR operations scorecard. Clearly articulating the role’s aspirational goals may help attract better candidates.

[RMP scorecard examples available here: CAO, chief of staff, director of student supports, principal, assistant principal of instruction, and teaching fellow.]

Probe for Evidence and Alignment with the Scorecard

The best predictor of future performance is past performance. During every step of RMP’s selection process — from the resume screen all the way to the final reference checks — Sara and the hiring manager actively evaluate:

The skills in which the candidate already has demonstrated strength (as evidenced through past performance and work samples)

The alignment between the candidate’s strengths and the skills required for this role (as defined in the scorecard)

Example of RMP’s Selection Process

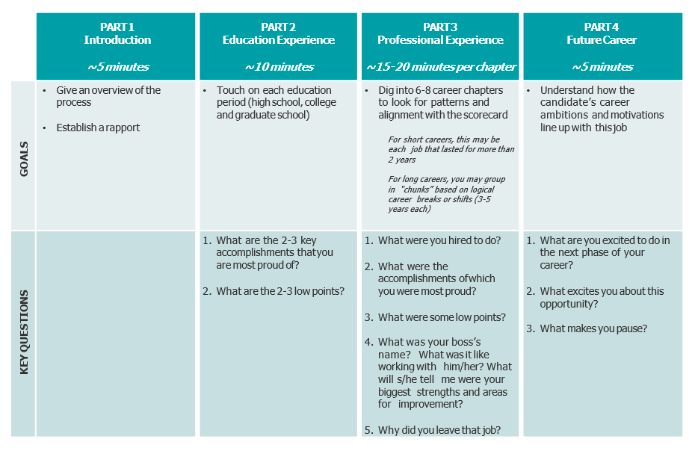

RMP utilizes a structured interview process, in which each candidate is asked the same set of questions to allow for better comparisons. Questions primarily are “backward-looking” (to understand how a candidate did act in a real-life situation) instead of “forward-looking” (to assess how a candidate might operate in a hypothetical scenario).

During the competency interview, for example, RMP focuses on behavioral questions that force candidates to share anecdotes of when they exhibited the skills required for the role. “If you want to know if a candidate has a growth mindset,” says Sara, “ask her to describe a challenge she faced, how she approached it, and what she would do differently in retrospect.”

Example of RMP’s Assistant Principal Competency Questions

Just because a candidate hasn’t held the exact role before doesn’t mean she isn’t a good candidate — the hiring manager still can look for evidence of certain behaviors. If a teacher is applying to be director of community engagement, a question might be: “Tell me about a time when you built a relationship with a parent or community member.”

The “deep dive” interview, in turn, helps the hiring manager identify observable patterns, behaviors, or red flags by asking a series of five questions for every major education or work experience since high school:

What were you hired to do?

What were the accomplishments of which you were most proud?

What were some low points in this role?

What was your boss’ name? What was it like working with her? How would you rate the team? What will she tell me were your strengths and areas for improvement when I call her as part of this interview process?

Why did you leave that job?

Sample “Deep Dive” Interview Agenda

This process can take 1.5–3 hours, depending on the length of a candidate’s career and the role level. RMP shortens it to 45 minutes for candidates who are coming straight from the classroom. Rather than perceive it as onerous, candidates often appreciate the opportunity to share more about who they are. (See a “deep dive” structured interview guide here.)

“If you do the deep dive and competency interviews well,” says Sara, “you shouldn’t walk away with unanswered questions. Don’t be afraid to probe!” Sara or James try to sit in on every deep dive in order to model how to do this well for the hiring manager.

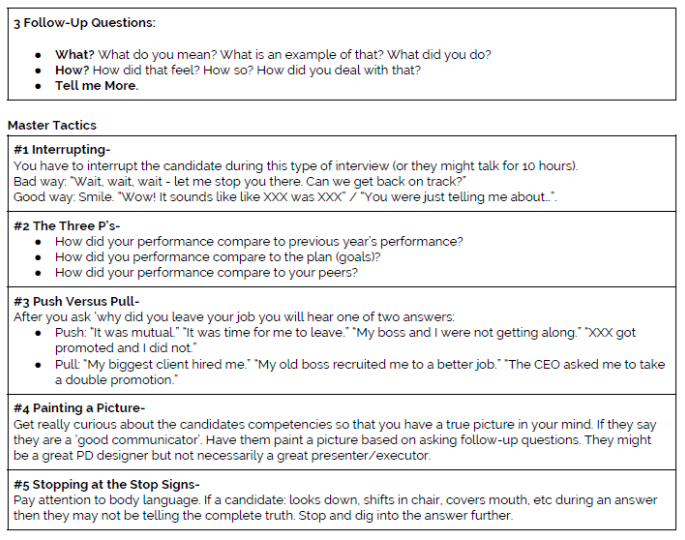

Sample RMP Interview Tips

In addition, RMP asks candidates to complete a role-related performance task during the selection process. For an assistant principal of instruction role, this is a classroom observation, mock coaching conversation, and debrief. For a director of student supports role, this could be reviewing RMP’s student services strategy and outlining its strengths and areas of opportunity. (See RMP’s assistant principal of instruction interview guide.)

After each touch point, Sara and the hiring manager add evidence and rate candidates on a 1–5 scale for every outcome and competency outlined in the scorecard. These ratings determine which candidates should move to the next round — and which areas need examination in further interviews or in reference checks. Reference checks are critical to validate the scorecard ratings (see Topgrading’s “threat of reference check,” or TORC, overview here).

The scorecard mitigates unconscious bias by serving as a clear rubric for evaluating candidates. Hiring managers point back to it as the quantitative measure of fit. It also keeps stakeholders aligned on hiring decisions.

Sara warns: “Don’t hire for what you don’t need. I mistakenly hired someone who was a really compelling candidate — just not for that role.”

Structure Development Based on the Scorecard

Rarely will a new hire be rated a 5 for every competency or outcome on the scorecard. “I help the hiring manager think about the nice-to-haves vs. the must-haves — and what we can actually train people to do,” shares Sara.

For example, RMP may decide that it is hard to teach a new hire how to be a good influencer or motivator but that gaps in special education expertise potentially can be mitigated through an external training program. RMP creates an individualized 30/60/90-day onboarding and development plan, informed in part by the new hire’s scorecard ratings.

“We also use scorecards as the foundation for our goal-setting and performance discussions,” adds James. Employees identify and are evaluated on 3–5 position-specific competencies, two organization-wide core competencies, and a small number of individual priorities and key results. (See sample RMP assistant principal of instruction evaluation form.)

Example of RMP’s Performance Evaluation Process

James was thoughtful about how to introduce scorecards to RMP during the initial pilot phase: “We started with anyone that I was hiring so I could test the process first. Then we used it to hire new principals.” RMP worked with Allison Rogovin, a consultant with Topgrading experience, during the pilot.

RMP now creates scorecards for most central office positions (director-level and above), as well as some school-based roles (principals, assistant principals, office staff, teacher leaders, and teaching fellows). IDEA, Mastery Charter Schools, and Ednovate have also piloted scorecards. (See Ednovate’s director of finance and budgeting scorecard and interview guide.)

Despite the change management, hiring manager training, and time required to implement scorecards effectively, both Sara and James agree that scorecards have transformed RMP’s hiring process for the better. As Sara notes, “We’re learning things about candidates during the new interview process that we wouldn’t have caught in our old model.”